IN CONVERSATION: Fashion Revolution

We were grateful to catch up with the Fashion Revolution team about this year's theme Money, Fashion, Power and explore how we all can influence the fashion industry, for the better.

Can you tell us a little about Fashion Revolution and why it was founded?

Fashion Revolution was founded in the wake of the Rana Plaza disaster in 2013. We are one of the largest fashion activism movements, mobilising citizens, brands and policymakers through research, education and advocacy. Our vision is a global fashion industry that conserves and restores the environment and values people over growth and profit.

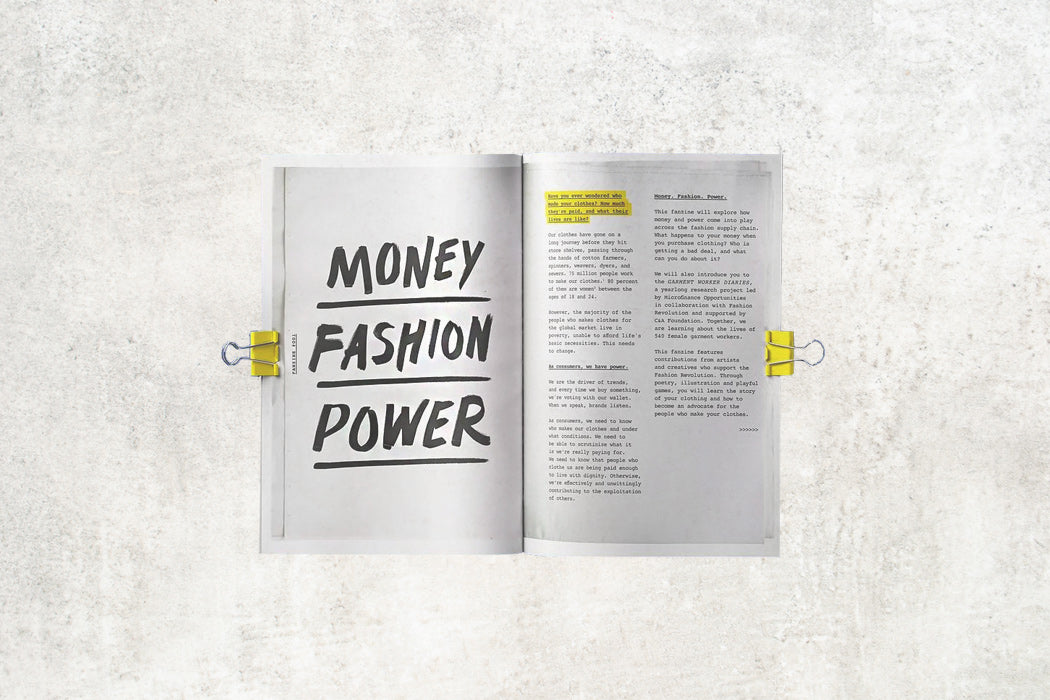

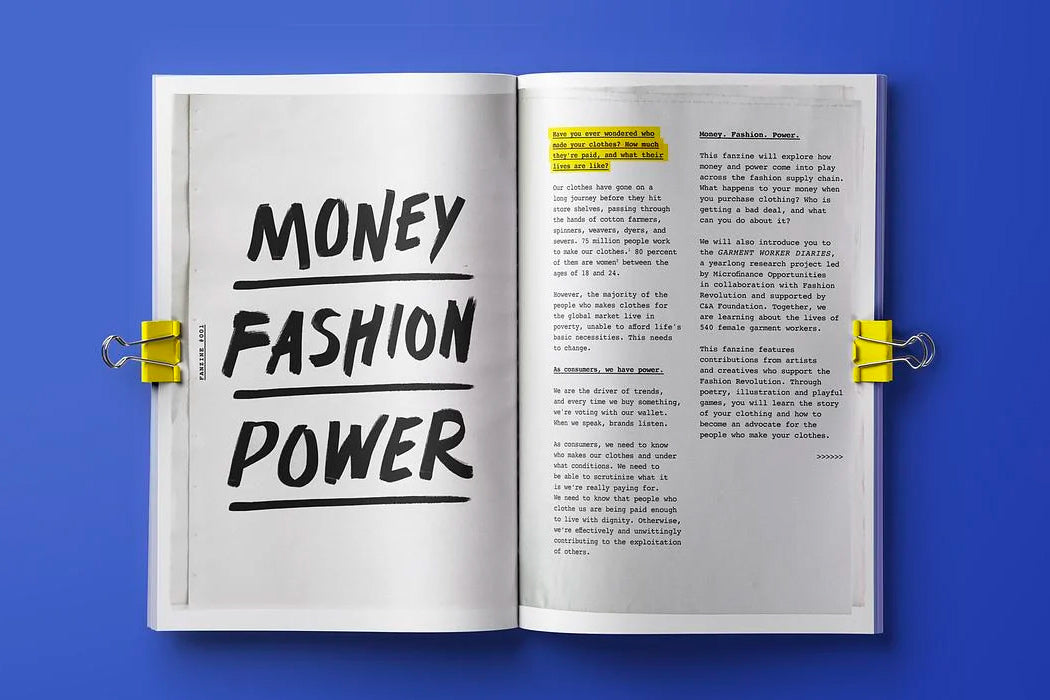

The theme for Fashion Revolution this year is Money, Fashion, Power. How can we (as businesses and as consumers) influence change within the fashion industry right now?

Fashion Revolution Week (FRW) is the annual campaign bringing together the world’s largest fashion activism movement for seven days of action surrounding the anniversary of the Rana Plaza factory collapse. This year, the campaign will run from Monday 18th-Sunday 24th April, with the aim to collectively reimagine a just and equitable fashion system for people and the planet.

The theme for Fashion Revolution Week 2022 is MONEY FASHION POWER, builds on the knowledge that the mainstream fashion industry relies upon the exploitation of labour and natural resources. Wealth and power are concentrated in the hands of a few, and growth and profit are rewarded above all else. Big brands and retailers produce too much too fast, and manipulate us into a toxic cycle of overconsumption. Meanwhile, the majority of people that make our clothes are not paid enough to meet their basic needs, and already feel the impacts of the climate crisis - which the fashion industry fuels.

“As we enter our 9th year, we will go back to our core, exposing the profound inequities and social and environmental abuses in the fashion supply chains. From the uneven distribution of profits, to overproduced, easily discarded fashion, to the imbalances of power that negate inclusion.

On the other hand, inspiring new designers, thinkers and professionals all over the world are challenging the system with solutions and alternative models. Fashion Revolution Week is all of this, scrutinising and celebrating fashion, globally and locally, wherever you are.” - Orsola de Castro, Co-founder and Global Creative Director, Fashion Revolution

This year, Fashion Revolution is calling on global citizens to rise up together for a regenerative, restorative and revolutionary new fashion system. Throughout Fashion Revolution Week, the groundwork will be laid down for new laws on living wages for the people that make our clothes, brands will be encouraged to shift their focus away from endless growth, and consumers will be inspired to scrutinise the real value of what we buy. To get involved, Fashion Revolution will provide the tools for people to write to their local policy maker about these issues, demand greater transparency in the fashion supply chain, support trailblazing small businesses and create their own fashion love stories to reconnect with the clothes they wear every day.

3 QUESTIONS TO ASK DURING FASHION REVOLUTION WEEK

1. #WhoMadeMyClothes Does the person who made your clothes deserve a living wage?

2. #LovedClothesLast How much did you pay for *insert fave clothing item here*? And how much is it worth to you?

3. #WhatsInMyClothes What would the world look like if brands restored systems instead of depleting them?

https://issuu.com/fashionrevolution/docs/fr_2022_getinvolved_citizens

It is not always easy to understand where / how garments are made. How can consumers shop with peace of mind regarding workers being paid fairly?

The vast majority of the people who make our clothes are not paid enough to fulfil their basic needs. The 2021 Fashion Transparency Index showed that only 27% of big brands disclose their approach to living wages for workers in the supply chain and just 2 out of 250 brands disclose data on the number of workers in the supply chain who are actually paid living wages.

Information that is publicly disclosed can be used by worker rights groups, trade unions and environmental groups to identify issues happening in supply chains and hold major brands to account. That is why transparency matters. It helps enable access to justice. Without transparency, achieving a sustainable, accountable and fair fashion industry will be almost impossible. With regards to how consumers can shop with peace of mind that garment workers are fairly compensated, the current level of living wage transparency makes this challenging, if not impossible.

The FTI 2021 revealed that fewer than 1 in 10 major brands publish a policy to pay their suppliers within 60 days, which is in line with the UK Prompt Payment Code commitments. Very few brands (just 6%) disclose how long after delivery they pay suppliers, on average. For the brands that do disclose this data, their payment terms often ranged from 60 to 180 days after receiving their goods. This means that clothes are often being worn by customers long before brands pay the factories that made them.

Whilst we push for concerned citizens to use our FTI data to enable their activism, we understand that they also want guidance on what tools are accessible to them to make better purchasing decisions. With this in mind, our close collaborator Good on You is a great resource who rate brands using a very robust methodology which we at Fashion Revolution have provided input on. Further, our methodology is integrated with Clean Clothes Campaign’s Fashion Checker, which looks at brands’ transparency regarding wages paid to workers.

Those who visit the webpage are also invited to sign a petition demanding that brands pay their workers. In tandem with this, we also invite people to use Fashion Revolution’s email-a-brand tools, and ask #WhatsInMyClothes? To demand brands are transparent about the chemical and material inputs into our clothes and #WhoMadeMyFabric? To demand transparency on where the fabrics that make-up our clothes are made and under what conditions. However, the power and responsibility lies in the hands of brands and retailers because the easiest decision for a consumer to make is to not have to make a decision at all.

Brands should improve their policies, practices, outcomes and impacts to eliminate and phase out harmful business models and processes that harm human rights and the natural environment. We must move beyond the binary of fashion and sustainable fashion -- sustainable fashion should be the norm, not the exception.

We know there is a long road to fair fashion production everywhere but what good signs have you seen in the last year that things can change, for the better?

Over the last year, we have seen legislative proposals which tighten their grip on the fashion industry. Most recently, mandatory corporate sustainability due diligence legislation is coming to the EU. This means corporations who operate in the EU or have supply chains within the EU will need to identify and prevent any adverse impacts that their activities might have on human rights and the environment. Apparel companies with more than 250 employees and a net turnover of EUR 40 million worldwide will be liable under the proposal.

While the Directive has been criticised for not applying to 99 percent of companies, the remaining 1 percent are still responsible for producing mass volumes of clothing and holding the most influence within the industry. For example, in the FTI we review the world’s largest and most profitable brands and retailers because they have the largest negative impacts on people and the planet, and therefore have the moral imperative, as well as resources, to take action. We estimate that at least 200 brands included in the FTI are captured by this legislation, therefore creating potential for the Directive to have significant impact within the industry.

That being said, the Directive stipulates that companies are only responsible for those who they have ‘’established business relationships” with. Of course, apparel supply chains are mired in complex subcontracting agreements, meaning that the risks that arise from these informal business relationships will be missed from the legislation. At the same time, we are gradually seeing brands improve their disclosure.

'For example, back in 2016 when the Index was first published, luxury brands claimed they could never disclose where they source from due to competition but that has since changed.'

For the first time in 2021, luxury brands like Gucci are publishing their supplier lists - indicative of a cultural shift within the industry where transparency is more and more being embraced rather than feared. Nonetheless, we have a long way to go in terms of transparency, considering that the average score across all brands is just 23% and no brand scores above 80%.

Importantly, a score of 100% is not the ‘end’, but rather a vital starting point for accountability.

Comments